|

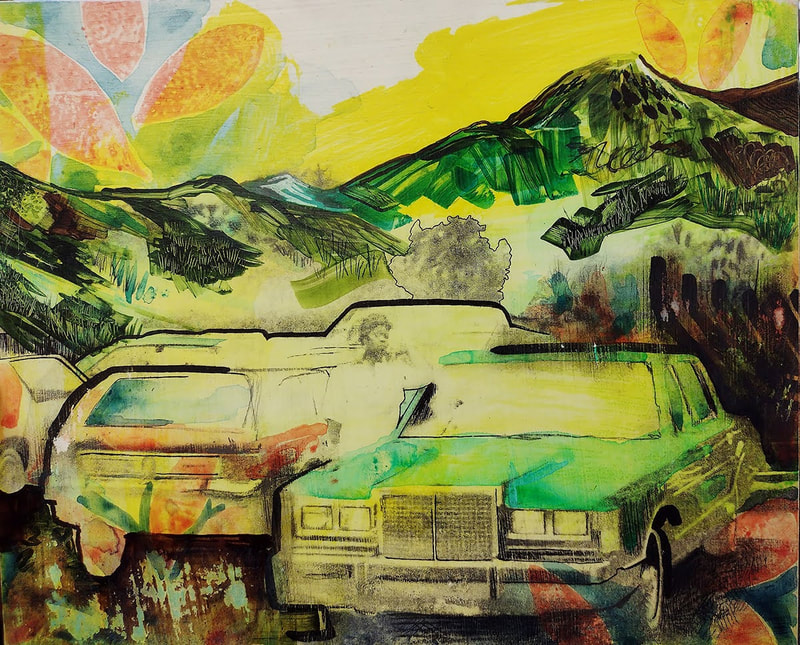

By Anya Shukla and Dilinna Ugochukwu Kaiser Louis sees his artwork as a way to honor his family lineage. Louis, the son of a first-generation Haitian immigrant, uses art to explore his family’s immigration and reflect on his personal experiences. What does it mean, Louis asks through his pieces, to speak French, English, and Creole but have never visited Haiti? In what ways am I connected to my heritage, and in what ways am I separated? He expresses these dichotomies through collage: taking photos, modifying them slightly in Photoshop, then adding physical layers of transfer, watercolor, acrylic, and pencil. This time-consuming process adds another dimension to his work: his pieces aren’t going to go away; “they’re not a photograph that can be deleted.” The hours he spends creating artwork is a tribute to his ancestral history. And Louis’ work pays off: his family loves his pieces, sometimes driving two hours to see one of his paintings. However, Louis did not always use his artwork to explore his personal heritage: “for a long time, my work wasn’t about me. It was just about Black culture.” This focus stemmed from his experience as one of a few Black students in his art-focused middle and high schools. Louis has attended arts school from a young age. “If I didn’t have those classes and teachers guiding me,” he noted, “my art wouldn’t be what it is today.” (And as his numerous artistic accolades can attest, his art is really, really good today.) Yet growing up, Louis never saw many artists who looked like him. “Everyone we learned about was either dead or an old white person.” “I didn’t see a lot of representation for Black artists when I was growing up, and a lot of my classmates didn’t either,” Louis said. “But the difference is how it affected me.” In eighth grade, Louis was the only student from his middle school accepted into an arts-focused high school. Although teachers congratulated him, one comment from a peer still sticks in his mind. “A kid said that I only got into that school because I was Black,” Louis recalled. That interaction had a significant impact. “I started to believe what he was saying… I didn’t feel like making artwork anymore.” After reflecting on that experience, Louis decided to return to art, but with a new purpose. He wanted to use his artwork to bring more representation to Black artists, Black lives, and Black culture. For his AP Portfolio, for example, he made portraits of influential Black people as an exploration of what it means to be Black. However, his drive to represent his heritage carried its own weight: “I felt like I had to promote these stories… it felt like it was another job.” If he had more classmates who looked like him, that might have eased the burden. “I wouldn’t feel like it’s on me to talk about this.” Now, Louis still remains dedicated to his craft—signing up for competitions and National Portfolio Day, determined to improve his work—but has realized that his art can explore his personal heritage alongside his race. He pushes back against teachers who want his work to be more “urban” and prioritizes his own artistic style. Louis believes schools and other institutions can combat racial inequity in the arts by opening up conversations and highlighting more voices. Everyone has a different perspective, so there needs to be “an open call: everyone should be invited to have this conversation.” He especially advocates for more diverse judging boards at competitions. Wherever they are in the artistic journey, Louis wants teens to keep making art, regardless of what other people may say. “At the end of the day, it’s your work. It’s personal to you.” Don’t be swayed by other people’s opinions or feel that you have to stay confined to a certain artistic genre or idea; “don’t make your work for anybody else.” All image credits to Kaiser Louis.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed