|

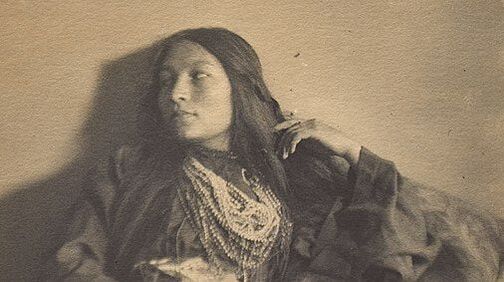

By Anya Shukla Be warned: this review reads more like an English essay than my previous snarkfests. Zitkála-Ša’s writing feels more formal (probably because this book was published a century ago), and my analysis reflects her tone. Sorry if you miss my “fun” voice… hopefully, it’ll be back next week. Review: Born in 1876, Zitkála-Ša, a member of the Yankton Dakota Sioux, began writing and publishing work in her early 20s. An accomplished activist and lecturer, Zitkála-Ša spent her entire life advocating for Native American rights: hosting voter registration drives, authoring articles about the exploitation of Indigenous people, and preserving Native culture. “American Indian Stories,” published in 1921, contains some of Zitkála-Ša’s finest work. Through three genres—nonfiction, fiction, and poetry—she details her culture, heritage, and the exploitation of Native and Indigenous peoples. Zitkála-Ša’s clear, honest stories read as an antithesis to the typical portrayal of Native Americans in popular Western literature. “Little House on the Prairie” this book is not. Rating: 4/5. What I Loved: I enjoy a good throughline as much as the next gal, and Zitkála-Ša effortlessly connects the three sections of this book through two themes, Christianity and nature. Christian missionaries take Zitkála-Ša to Christian-run boarding school, where she faces adults who don’t value their charges’ wellbeing and culture. One Christian woman, charged with noting down the children’s absences, does not care about the source of their tardiness, “no matter if a dull headache or the painful cough of slow consumption had delayed the absentee” (pg. 80). Upon seeing one of her classmates die of sickness with a Bible near her bed, Zitkála-Ša grows bitter, feeling that her guardians care more about converting her peers than supporting them: “I blamed the hard-working, well-meaning, ignorant woman who was inculcating in our hearts her superstitious ideas” (pg. 81). The theme of religion pervades “American Indian Stories,” from a fictional tale about a soft-hearted Sioux whose people reject him after he returns as a Christian missionary to a poem that reminds a former Christian teacher that “old race problems, Christ e’en failed to expel” (pg. 225). Zitkála-Ša’s mother even warns her daughter: “Beware of the paleface… He is the hypocrite who reads with one eye, ‘Thou shalt not kill,’ and with the other gloats upon the suffering of the Indian race” (pg. 106). While this generalization does not describe every Christian during this time period—some did advocate for Native people—many were “driven” by their religion to “educate” Native Americans… and in doing so, often robbed them of their culture and family. Zitkála-Ša also sees nature as holy, a form of religion: “I prefer to their dogma my excursions into the natural gardens where the voice of the Great Spirit is heard in the twittering of the birds, the rippling of mighty waters, and the sweet breathing of flowers” (pg. 119). According to an article from Harvard’s Pluralism Project, to Native Americans, “land was not a source of private profit but of life, including the life of the spirits. Some lands were also sacred.” This context, along with Zitkála-Ša’s clear passion for nature, gave me new insight into the devastation wrought by the forced relocations alluded to in this book. What I Didn’t Love: I honestly can’t put my finger on why “American Indian Stories” doesn’t get a 5/5 from me. Perhaps it’s because I enjoyed the nonfiction and fiction sections more than the poetry? Because Zitkála-Ša published this book in 1921, and its writing style feels more reserved because of its age? All of the above? Everything Zitkála-Ša writes is real and pretty and lyrical, but her work doesn’t knock my socks off. Just personal preference. BIPOC Book Connections: Both “The Marrow Thieves” and “American Indian Stories” address the impact of Indian boarding schools (I use the word “Indian” here because that is the historical term associated with these schools). However, the books examine this topic from two different angles: the former imagines how these schools could reappear in the future, while the latter recounts their influence in the past. Because Zitkála-Ša wrote “American Indian Stories” in the early 1900s, I feel distanced from her experiences. I gain a strong first-person description of a residential school’s impact on a Native youth, but I don’t feel compelled to make changes in the present. In contrast, the reemergence of Indian boarding schools in “The Marrow Thieves” forces a non-Native reader to honestly assess and reckon with the treatment of modern-day Native and Indigenous people. If I was an educator, I’d pair these books together. Read “American Indian Stories” for historical insight, then draw on that information to better understand the futuristic world of “The Marrow Thieves.” A Quote I Would Like On Goodreads: “To my innermost consciousness the phenomenal universe is a royal mantle, vibrating with His divine breath. Caught in its flowing fringes are the spangles and oscillating brilliants of the sun, moon, and stars” (pg. 119). Up next: “Woke Racism” by John McWhorter.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed